Buildings as Material Banks: facilitating the circular value chain

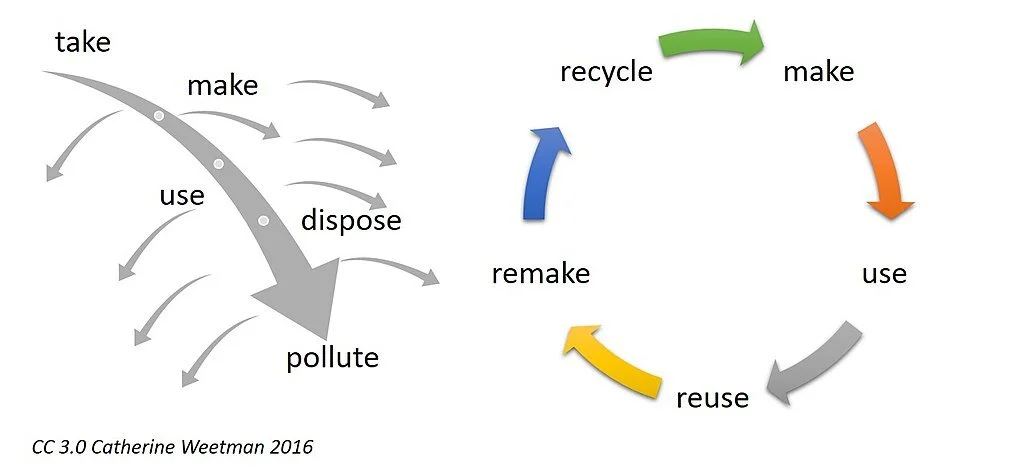

A key tenet of sustainability is the circular economy, whereby products are designed to be reusable and easy to repair. As relatively recently as 2014, the UK was producing 202.8 million tonnes of waste, of which 59% was from construction, demolition and excavation. More positively, the recovery rate for non-hazardous construction and demolition rate in 2014 was 89.9%, nearly 20% higher than the EU target for 2020, plus hazardous waste has been reduced over the last decade. Traditionally, economies were linear, with materials being thrown away. This isn’t sustainable – hence the move to value chains predicated upon reusing or regenerating materials. There are environmental, financial and social benefits to getting this right. Indeed, throwing materials away actually turns something that could be an asset into a cost.

Catherine Weetman, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

One way to drive the circular economy is to increase the value of buildings – and in the medium to long term. This is where BAMB (Buildings as Material Banks) comes in. The concept is simple enough: design buildings dynamically and flexibly to create a circular building value chain and push the shift to a circular building sector. This requires disassembling buildings when they are no longer required and re-using the materials. The idea is to reduce the use of virgin resources and reduce construction and demolition waste in favour of re-use. The most well-known trialling of the methodology was the EU-funded BAMB project that began in 2015, involving 16 partners and ending in the run up to the EU Horizon Framework Programme in 2020. The methodology, though, is an ongoing one, so this was not some sort of one-off project.

It is a systemic concept, aimed at all stakeholders: from policy makers to the smallest construction company. As part of this, the project had evidence-based forms of monitoring that functioned as value-adding frameworks, such as Materials Passports, Reversible Design Protocols and Circular Building Assessments, which will be discussed below. One notable aspect is the relative level of choice available for parties getting to where everyone needs to be, as this quote makes clear:

“From an inspiring and clear vision, different pathways to the desired system can be outlined. This ‘back-casting’ exercise (returning to the present from an image of the future) results in a number of strategic paths that can be followed to co-establish the new system. These pathways constitute a portfolio of options, which comprises diversity and choice, a highly significant characteristic of stable and resilient systems.”

While this is a recipe for system change, there are many paths to it, making it a holistic plan with room to manoeuvre. At the macro level, BAMB fits in to the demands of the United Nations 2030 Agenda, which has 17 sustainable development goals, of which 10 are facilitated by the BAMB project. To facilitate monitoring, there is a ‘State of the Art’ report, which investigates “the main technical, economic, financial, environmental, legal, spatial and logistic drivers/causes for the known (type of) actor within the current value chain”.

Materials passports and Reversible Building Design were the twin pillars of the project. The former function as a one-stop shop for data describing materials use and aid in bridging the information gap between the relevant players, resulting in better life cycle management, assessment and certification. The project encompassed over 300 different passports for differing products, components and materials and are aptly explained in this short film.

Reversible Building Design enables repair, re-use and recovery of materials, components and products through ensuring that specific aspects – such as floors or windows – can be accessed without damaging other parts of the building. It is the method of design that then allows the Material Passports to do their jobs. It is here where the theory behind BAMB can be seen: buildings which function as banks of valuable materials that are easy to access and recover. Buildings that are reversible are hugely important in the circular economy, in particular larger units such as office and apartment blocks. While it is becoming more common, it’s still not the norm in the sector, so there is work to be done.

Let’s have a look now at what lessons were learned during the project. There was a lack of life cycle and circularity data: specifically, disparate data sets were scattered throughout the value network, plus at the design stage, a lot of data is unavailable, for the simple reason that it relates to the future of the building. Certain assumptions have to be made by the assessor, which leads to unclear assessment results. Moreover, it is difficult to find data to manage the benefits of policy measures. Another issue was competing data platforms, which potentially could detract from the efficacy of the materials passports. Further issues involve financial risks, a lack of clarity at the start of projects about who the owner of a building is going to be and determining the residual value of buildings that could be in use for many years.

This why the real-time BAMB building experiments were important as technical solutions could be tested within an agreed time frame that would provide results and showcase good and bad practice. Even so, the BAMB project made recommendations for further experimentation, in order to make the move from innovation to transitioning to the circular economy and from single building cases to large scale projects. This has come to fruition in the city of Reburg, which has been designed as the the world’s most circular city. As the name suggests, it’s a (not yet built, of course) city entirely predicated upon reusing materials – ‘where the circular economy comes to life’. This is from the BAMB website:

“Imagine a city where the concept of ‘buildings as material banks’ is fully developed:

· A city where buildings are designed to be easily transformed and disassembled in to smaller parts for other purposes!

· A city where information on buildings and building products is shared in order to get building materials and products into valuable technological and biological cycles and eliminating the concept of waste

· A city where circular businesses are thriving by creating mutual benefits for building professionals, manufacturers, financers and building users through sustainable product service systems.

Something for the far future, you would think?”

If all hands can be put to the wheel, it is feasible that we can be living in cities like Reburg in the not too distant future: the imagination, talent and technology is there, so if the will can match that, then we could see a real Utopia in our lifetime.